|

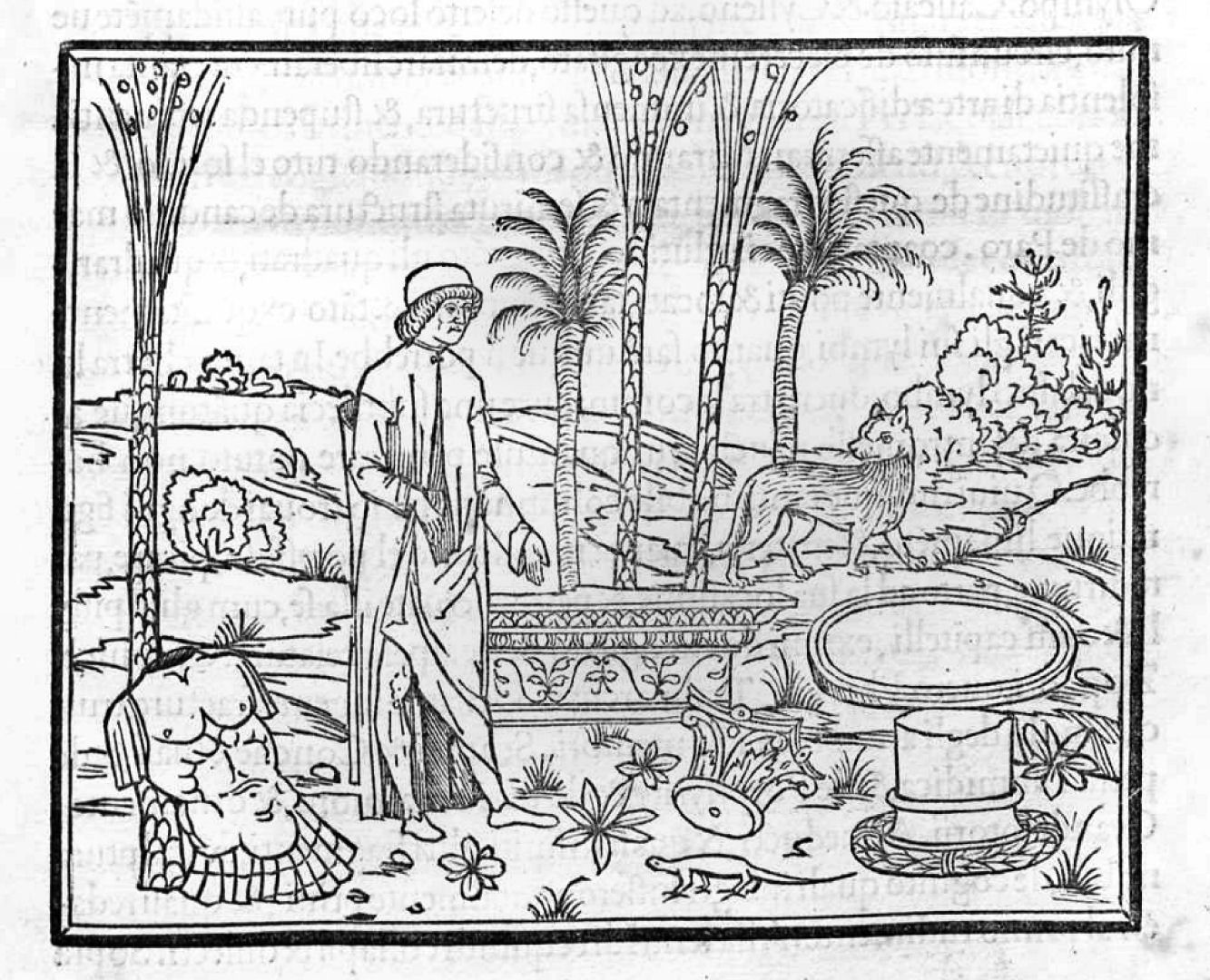

Poliphilus dreams of finding himself in a dark and perilous wood, and of coming out of it thirsty, to appease nearby a water stream. He reaches a pleasant place, where, under the shadow of an oak tree, he narrates a new adventure.

|

«La

spaventevole silva, et constipato nemore evaso, et gli primi altri

lochi per el dolce somno che se havea per le fesse et prosternate

membre diffuso relicti, me ritrovai di novo in uno più delectabile

sito assai più che el praecedente. El quale non era de monti

horridi, et crepidinose rupe intorniato, né falcato di strumosi

iugi. Ma compositamente de grate montagniole di non tropo altecia.

Silvose di giovani quercioli; di roburi, fraxini et Carpini, et di

frondosi Esculi, et Ilice, et di teneri Coryli, et di Alni, et di

Tilie, et di Opio, et de infructuosi Oleastri, dispositi secondo

l’aspecto de gli arboriferi Colli. Et giù al piano erano grate

silvule di altri silvatici arboscelli, et di floride Geniste, et di

multiplice herbe verdissime, quivi vidi il Cythiso, la Carice, la

commune Cerinthe. La muscariata Panachia el fiorito ranunculo, et

cervicello, o vero Elaphio, et la seratula, et di varie assai nobile, et de molti

altri proficui simplici, et ignote herbe et fiori per gli prati

dispensate. Tutta questa laeta regione de viridura copiosamente

adornata se offeriva. Poscia poco più ultra del mediano suo, io

ritrovai uno sabuleto, o vero glareosa plagia, ma in alcuno loco

dispersamente, cum alcuni cespugli de herbatura. Quivi al gli ochii

mei uno iocundissimo Palmeto se appraesentò, cum le foglie di

cultrato mucrone ad tanta utilitate ad gli Aegyptii, del suo

dolcissimo fructo foecunde et abundante. Tra le quale racemose

palme, et picole alcune, et molte mediocre, et l’altre drite erano

et excelse, electo Signo de victoria per el resistere suo ad

l’urgente pondo. Ancora et in questo loco non trovai incola, né

altro animale alcuno. Ma peregrinando solitario tra le non densate,

ma intervallate palme spectatissime, cogitando delle Rachelaide,

Phaselide, et Libyade, non essere forsa a queste comparabile. Ecco

che uno affamato et carnivoro lupo alla parte dextra, cum la bucca

piena mi apparve » .

|

«Scampato alla spaventosa selva e alla fitta boscaglia e lasciati i trascorsi

paesaggi, con le membra stanche e prostrate per il dolce sonno che

le aveva pervase, mi ritrovai in un luogo molto più ameno del

precedente. Il quale non era contornato da orrendi monti e scoscese

rupi, né era tagliato da aspre giogaie. Ma composto da grandi

montagne non troppo alte ricche di selve di giovani querce, di

roveri, frassini, carpini, di ischi frondosi e lecci, di teneri

noccioli, ontani, tigli, aceri, sterili oleastri disposti a seguire

l’andamento degli arboriferi colli. E giù nella valle vi erano

grandi selve di altre piante selvatiche, di floride ginestre, di

molte erbe verdissime. Qui vidi sparsi sui prati il citiso, la

carice, la cerinta comune, la panachia muscaria, il ranuncolo

fiorito, il cervicello o elafio, la serratula, molte specie assai nobili e molte altre

semplici ed ignote erbe sparse nei prati. Si offriva tutta questa

lieta regione coperta di verde.

Poco oltre trovai una piaggia

sabbiosa e piena di ghiaia, punteggiata qua e là di radi cespugli

erbosi. Qui si presentò agli occhi miei un delizioso palmeto, le

cui foglie sono tanto utili per gli Egizi, dal suo dolcissimo frutto

fecondo ed abbondante. Per i cui rami, alcuni piccoli e mediocri,

altri dritti ed eccelsi, fu eletta simbolo di vittoria a causa del

suo resistere anche sotto un gran peso. Ancora, in questo luogo, non

trovai abitanti né animale alcuno. Ma camminando solitario tra le

non dense ma intervallate palme, pensando a Rachelaide, Phaselide e

Libyade, non esserci forza a queste comparabile. Ecco che, dalla

parte destra, mi apparve un affamato e carnivoro lupo con la bocca

piena ».

|

Poliphilus dreams of falling asleep aided by the coolness of a tree and of walking in solitude in a place punctuated by «not dense, but interspersed palms» , in a scenery of ancient ruins which turns his double dream into a prelude of his archaeological dream, where references to the Antique are numerous.

The vegetation made of palm trees encapsulates many layers of meaning. It is, indeed, both a topographic reference, as suggested by Calvesi , which help us identifying its location with the Lazio coast where palms grow spontaneously, and a hint to Egyptian culture, in which this plant is often associated with the god Thot, king of time , and it is also held in the right hand of the king of the afterlife Anubi . Lastly, intertwined palm branches form the sandals of the goddess Isis, as well as the wreaths of her initiated . The symbols of victory and strength coexist in this plant, which is robust and evergreen.

Making references to Aulus Gellius, Aristotle and Plutarch, Erasmus, in his Adagia, writes «palmam ferre» to indicate the degree of fatigue tolerance of its wood, which, even under a heavy burden, does not break nor bent, as also underlined by Leon Battista Alberti in his De Re Aedificatoria and by Francesco Colonna elsewhere in the Hypnerotomachia .

In the Emblemata, Henkel and Schone provide us with the image of a palm assaulted by many chubby boys, who try to conquest its scented dates . However, only those climbing fiercely would gain the fruits, as a reminder to hold on tight against the difficulties to achieve goals. Ultimately, the personification of Victory has got a palm among her insignia, alongside the eagle, symbol of strength, and the laurel, an evergreen.

Nevertheless, the meanings unveiled by the palm tree are more than just two. There is a third one, spread during the Christian era but rooted in antiquity: resurrection. An antique belief associates the palm with immortality and recounts that the phoenix which is about to die and reborn chooses the palm for its last nest, which is built on top of the tree. According to an ancient legend, narrated by Pliny, the tree burns along with the phoenix, to then spectacularly reborn from its hashes . The legend is further supported by a linguistic correlation between the Greek terms for «phoenix» and «palm», both written «φοινιξ» .

The verse on a medal of 1526 circa, carved for the Duke of Urbino Francesco Maria della Rovere, is especially interesting. It shows a palm with the branches bent by the weight of a stone and a cartouche hosting the verse «inclinata resurgo» .

While he walks, Poliphilus is frightened by a ravenous she-wolf that blocks his way to the right, so that he feels his hair curling on his head but cannot scream.

Surronded by ancient ruins, the she-wolf may suggest an immediate reference to the myth of the founding of Rome. However, if we pay attention to the pose of its body and the ferocity of its expression, we may assume that it encapsulates a far more complex and less simplistic meaning. The wolf has always been a much discussed and two-fold symbol: generative on the one hand, and destructive on the other.

In ancient Greece, it was consecrated to Apollo, god of the sun, because the latter attracts the flocks with his sunrays, as much as the animal captures and kills the beasts. Moreover, the wolf has a good sight during the night, which enables it to hunt and to metaphorically defeat the darkness much as sunlight does. Especially for this divine virtue, a beautiful metal wolf is host in the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. According to the myth, Latona, pregnant with Jupiter’s son, was tuned into a she-wolf, which then gave birth to the god of the sun. It was also believed that a wolf killed a thief who was trying to rob a temple, thus preserving its treasures . This animal has the power of generating noble and long-lasting lineages, such as the Roman one, as testified by some images which portray it alongside the label «suprimenda semina» . Coming back to the actual she-wolf which frightens Poliphilus, the shape of its body, presented backwards, is to be found in a hieroglyphic examined by the Egyptian Horapollo, who interprets it as a symbol of hostility and adversity, that is precisely what the animal is embodying for the protagonist of the Hypnerotomachia .

The she-wolf is at the same time threatening and fierce, watching over and protecting antiquities as if they were its «Roman sons», already dismantled by time. It ferociously blocks Poliphilus’ way, creating an immediate literary parallel to Dante’s same beast, which prevented the poet from embarking on his journey.

Alongside the palm, which has been already discussed at length, the lizard, another animal appearing in the landscape, is a symbol of rebirth, as it spontaneously regenerates the caudal vertebrae once they are cut. In classical mythology, this animal has ambivalent meanings. A symbol of wisdom and success, it was considered an emblem of the god Hermes and the Egyptian Serapis. At the same time, however, it was associated with snakes, with which it shared the chthonic and most obscure sides of their symbolism. It was commonly believed by the Romans that the lizard hibernated during the winter to get awakened during the spring; thus, it gained a symbolic meaning in the funerary context, for it represented death and rebirth and, often, it was reproduced in this context on Roman tombstones or, connected to the theme of sleep, next to images of sleeping putti. As for alchemists’ connections between lizards and lust, this would depend on some properties of the reptile, which can stay long hours sunbathing on rocks and can easily get in and out ravines, thus representing «telluric fire», that is basic sexuality .

The «ruinous» landscape surrounding the protagonist is permeated with an «ill-treated» Rome, with acephalous busts, broken columns, and scattered architraves and capitols. This brings to mind the discourses of several humanists, who, while visiting the ancient Forum (then buried), lamented the carelessness for the antique, which declassed the city and deprived it of the trophy of the Renaissance, conversely gained by Florence.

Poggio Bracciolini, Apostolic Secretary to Martin V (Oddone Colonna) and faithful to Cardinal Prospero, Francesco Colonna’s uncle, reports in his De Variaetate Fortunae that Oddone Colonna observed Roman ruins from the Capitol. Among those, Bracciolini also mentions Palestrina, the seat of Francesco Colonna, in his meditations over the instability of fortune .

In 1700, Piranesi succeeded in turning this «ruinism» into Roman archaeological poetry, philosophical speculation, and even protection of the cultural and archaeological heritage. The oval basin flanking the she-wolf has been interpreted by some scholars as an image of the Colosseum. However, its circular, rather than elliptical, shape seems to suggest a process of regeneration. The regeneration of a decaying city that can heal, the first ruin of which is Palestrina, home to Francesco Colonna.

In the Hypnerotomachia, circularity is a key theme, as witnessed by the shape of the isle of Cythera, a crucial site in the story.

Unifying the symbols discussed so far: the lizard, the ruins, the she-wolf and the oval basin, we realize that we are confronted with an initiation journey. A journey which origins in Poliphilus’ encounter with the she-wolf, a ferocious guardian of an ill-treated Rome and an allegory of the challenges an initiate has to face in order to drink to the source of wisdom. These difficulties can be overcome if one perseveres, much as the boys climbing on a palm tree to enjoy its fruits. This journey leads to regeneration and resurrection, for which ruinism is a premise for a reconstruction rooted in wisdom and knowledge. This invitation is not confined to 1499, with the printing of the Hypnerotomachia, but is especially valid today, at our times, when Italian cultural heritage is underestimated by national economy, whilst it should be better protected and boosted as a fundamental tool of substantial wealth.

Going back to our Poliphilus, whom my digressions left speechless in front of a wolf, he turns his gaze to a point where the hills seem to converge and he finds a «wondrous and portentous» topped by a mighty obelisk.

Enchanted by such a magnificence, he gets closer.

NOTE

BIBLIOGRAFIA

ALBERTI

1989

Leon

Battista ALBERTI, De Re Aedificatoria, Milano, Il Polifilo,

1989.

ALCIATI

A. 1977

Andrea

ALCIATI, Emblematum liber, Hildesheim; New York, Olms, 1977.

APULEIO

2005

Apuleio,

Metamorfosi, a cura di

L. Nicolini, Milano, BUR Biblioteca Univ. Rizzoli, 2005.

BROEK

1972

Roelof

van den BROEK, The myth of the Phoenix, Leida, E. J.

Brill, 1972.

CALVESI

1980

Maurizio

CALVESI, Il sogno di Polifilo Prenestino, Roma, Officina

Edizioni, 1980.

CARTARI

1996

Vincenzo

CARTARI, Immagini degli dei degli antichi, Vicenza, N. Pozza,

1996.

COLONNA

F. 1499

Francesco

COLONNA, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, Venezia, A. Manuzio Sr.,

1499.

FERRARI

2006

Anna

FERRARI, Dizionario di

Mitologia Greca e Latina,

Torino, UTET, 2006.

HENKEL

– SCHONE 1976

Arthur

HENKEL – Albrecht SCHONE, Emblemata : Handbuch zur Sinnbildkunst

des XVI und XVII Jahrhunderts, Stuttgart, J. B. Metzler, 1976

HORAPOLLO

L'EGIZIANO 2002

Horapollo

l’Egiziano, Trattato sui geroglifici,

a cura di Franco CREVATIN e Gennaro TEDESCHI, Napoli, Il

Torcoliere, 2002.

See in the BTA:

Icoxilòpoli - LE XILOGRAFIE DELL'HYPNEROTOMACHIA POLIPHILI

Partial report of the Researches of DogTalkingBook - CaroGuimus9 - Robotic Dog Museum Guide for Blind Children (and Adults) dated December 13th 2018 -

First Caroguimus9 Video Kit in English language

|